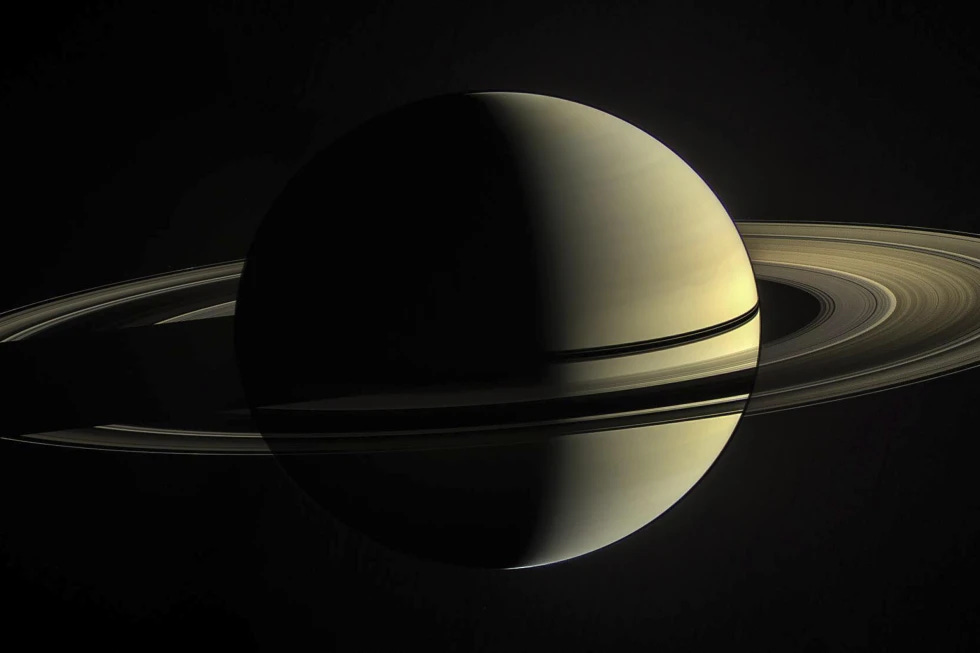

Saturn’s Rings May Be as Ancient as the Planet Itself, Study Finds

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (AP) — A new study challenges the long-held belief that Saturn’s iconic rings are relatively young. Instead of being around 400 million years old, as previously thought, the icy r

A Japanese research team led by Ryuki Hyodo from the Institute of Science Tokyo published their findings on Monday, suggesting that the rings could be much older than previously believed. The study proposes that the pristine appearance of the rings, far from indicating their youth, may be due to their ability to resist contamination by space debris.

For years, scientists assumed the rings were between 100 million and 400 million years old, based on observations made by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft before its 2017 mission end. Cassini's images revealed that the rings were not darkened by the impacts of micrometeoroids — tiny particles of space rock — which led researchers to conclude that the rings formed well after Saturn itself.

However, the new study, which utilized computer modeling, suggests that when micrometeoroids collide with the rings, they vaporize without leaving much debris behind. The resulting charged particles are then drawn toward Saturn or dispersed into space, preventing any buildup of dust or grime on the rings. This discovery undermines the theory that Saturn’s rings are relatively young and helps explain their flawless appearance.

Hyodo and his team suggest that the rings might fall somewhere in between the extremes of a 400 million-year age and the full 4.5 billion years, potentially making them about 2.25 billion years old. The research also takes into account the chaotic conditions of the early solar system, which would have created an environment conducive to the formation of Saturn's rings.

Given the tumultuous early solar system, Hyodo believes it’s more likely that Saturn's rings formed closer to the planet’s formation rather than much later.

The study, published in Nature Geoscience, challenges existing theories and opens up new possibilities for understanding the formation of the solar system’s most famous planetary rings.

This research was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.