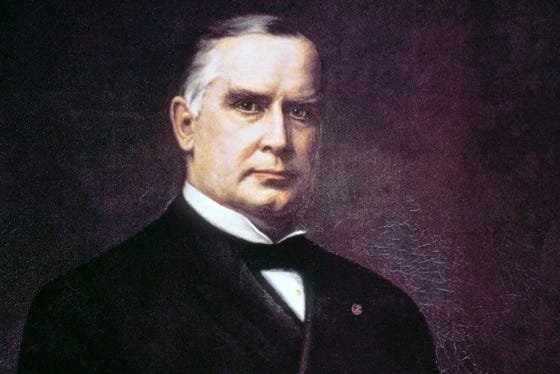

McKinley Descendant Suggests Compromise After Trump Orders Denali Renaming

President Trump’s move to rename North America's tallest peak after William McKinley faces opposition, but a McKinley descendant proposes a balanced solution.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — President Donald Trump has reignited a long-standing debate with an executive order that seeks to rename Denali, North America's tallest peak in Alaska, to Mount McKinley, in honor of the 25th U.S. president. While some celebrate the move, it has sparked significant opposition, particularly in Alaska, where many residents and lawmakers resist changing the mountain’s name back to McKinley.

Massee McKinley, a great-great nephew of President William McKinley, expressed strong support for the decision, calling it a well-deserved tribute to his ancestor’s leadership and integrity. “He deserves to have the mountain named after him,” McKinley said Thursday. “He had unparalleled integrity. People respected him.”

However, the move has drawn criticism, with Alaska’s two Republican senators, Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, both voicing their objections. McKinley has suggested a compromise to ease tensions: renaming the mountain Mount McKinley, while maintaining the name Denali National Park and Preserve. “The international community is always going to know the entire park and the mountain as Denali, and we don’t dispute that,” McKinley said. “But from a national perspective, I believe we can strike a balance.”

Trump’s executive order outlines this potential compromise, specifying that the national park surrounding the mountain will retain its original name, Denali National Park and Preserve. The proposal would allow the mountain itself to be renamed Mount McKinley while preserving the historic recognition of Denali in the park's name.

The mountain, standing at 20,310 feet, was first recognized as Mount McKinley by the federal government in 1917. Prior to that, Indigenous groups, including the Athabascan people, had their own names for the peak, with Denali meaning “the tall one” in their language. In 2015, the Obama administration officially recognized the mountain as Denali.

Trump, during his first term, had already suggested renaming the peak to honor McKinley, a move that was opposed by local Alaskan leaders. Murkowski and Sullivan have reiterated their stance, arguing that the name Denali holds deep cultural significance. In a video post on X, Sullivan said, “I prefer the name Denali that was given to that great mountain by the great patriotic Koyukon Athabascan people thousands of years ago.”

The debate also has personal undertones, with Sullivan recalling a 2017 conversation with Trump in which he said, “If you change that name back now, my wife, who is of Athabascan descent, is going to be really, really mad.” Trump reportedly agreed to leave the name Denali in place at the time, but now, with a new administration, the debate has been reignited.

While McKinley had no direct connection to Alaska, his name became associated with the mountain through a gold prospector, William Dickey, in the late 1800s, who was a supporter of McKinley. Over the years, Alaskans have used both Denali and Mount McKinley interchangeably. Sondra Shaginoff-Stuart, an associate professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage, noted that the name change to Denali in 2015 was a crucial step toward honoring Native people and their culture. “The mountain is so majestic. The name is a statement of recognition of Native people in their native language,” she said.

Massee McKinley, who serves as vice president of the Society of Presidential Descendants, expressed his pride in his ancestor’s legacy, adding that Trump had spoken to him about admiring McKinley’s business acumen and wanting to replicate that in office. “I figured this would happen, and it did come to fruition,” McKinley said. “I’d love to be a part of the signing process when they actually sign the proclamation for that.”

Alongside the Denali renaming, Trump’s executive order also proposes renaming the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America. The U.S. Department of the Interior has 30 days to update the nation’s geographic names database to reflect these changes.