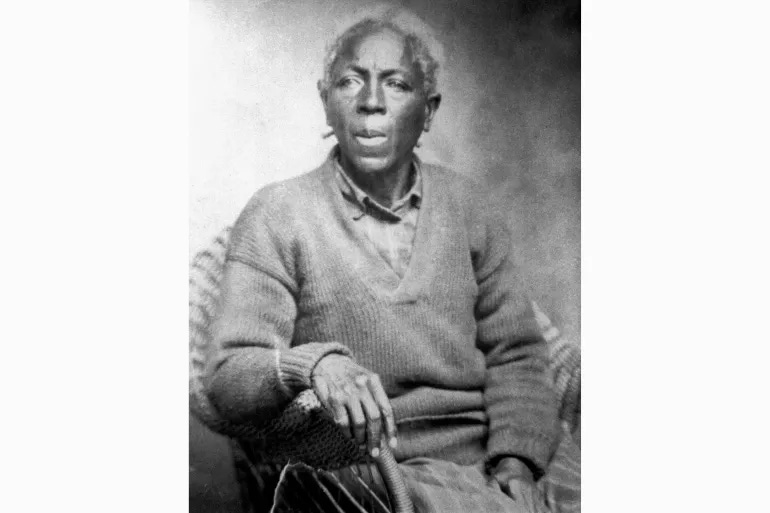

Honoring Matilda, the Last Survivor of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

January 13 marks 85 years since the death of Matilda, born Abake, a name meaning ‘born to be loved by all’ among the Tarkar people of West Africa.

On a brisk December morning in 1931, Matilda McCrear, a frail but determined elderly Black woman, embarked on a 24-kilometer (15-mile) journey from her Alabama homestead, seeking justice for the unimaginable horrors she had endured. At the time, she was in her mid-70s, but the walk to Selma’s court was crucial—she aimed to claim compensation for her past suffering.

Matilda's story began nearly a century before that fateful walk, far from the Alabama sharecropping fields. Originally named Abake, meaning "born to be loved by all," she was born around 1857 among the Tarkar people of Western Africa. At the age of two, Abake was taken from her family by soldiers of the Kingdom of Dahomey, located in present-day Benin. This was the start of a brutal journey that would span thousands of miles, as Abake, her mother Grace, and three older sisters were sold into slavery, becoming part of the final shipment of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic.

In 1859, Abake's family was bought by Captain William Foster, who operated the infamous Clotilda, the last known slave ship to transport human cargo to North America. Though the slave trade was outlawed by this time, Foster's ship made the perilous voyage, smuggling 110 enslaved people into Alabama. Upon arrival in the U.S., the captives were unloaded and forced into harsh labor, and Matilda was renamed before being put to work on a plantation near Montgomery.

Matilda and her family faced years of torment, and their lives were marked by the deep scars of slavery. When the Civil War ended in 1865, slavery was abolished, and Matilda's family was freed. But true freedom was elusive, as they were trapped in a cycle of economic exploitation under the sharecropping system.

As the years passed, Matilda’s life was marked by hardships, but she continued to persevere. In 1931, when rumors of compensation for illegally enslaved individuals reached her, she made the long journey to Selma’s courthouse, only to have her claim rejected. Despite this setback, a news article from the Selma Times-Journal captured a vivid picture of Matilda’s resilience. Her vigorous walk, her nearly white, braided hair, and her firm but gentle voice painted a portrait of a woman who had survived against all odds.

Matilda’s story is particularly remarkable because, even though she was a product of the brutal institution of slavery, she resisted its limitations. She never married, instead forming a long-term common-law partnership, and maintained many traditions from her African heritage, such as her distinctive Yoruba-style hair.

Her legacy is one of strength and endurance, not only as the last living survivor of the Clotilda but also as a symbol of the African-American struggle for justice and equality. While Matilda never saw justice for her suffering, her family continued to fight for civil rights. Matilda’s grandson, John Crear, recalls her funeral as one of his earliest memories, a poignant reminder of the tenacity passed down through generations.

In 1965, many of the systemic barriers that Matilda had faced began to fall, as the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act helped dismantle segregation and discriminatory practices. But Matilda’s life, and the struggles of her descendants, underscores the continuing fight for racial justice.

Matilda's story serves as a powerful reminder of the resilience and perseverance of those who survived the transatlantic slave trade and the long road toward justice and equality. Though she passed away in 1940, her impact lives on in the ongoing struggle for racial justice in the United States.